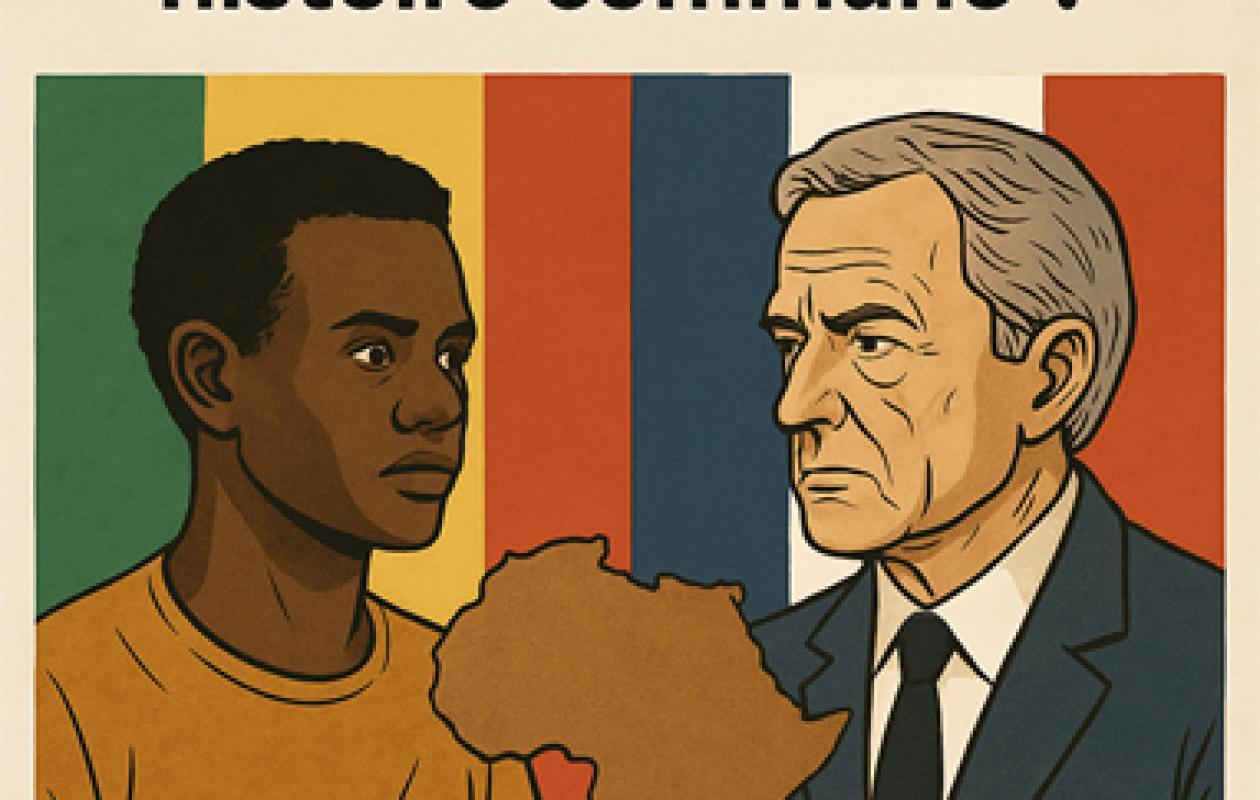

Le Sénégal et la France, histoire commune ?

The history of Senegal and France is primarily rooted in colonial logic. French rule imposed a language, administration, and economy geared toward exports. The structures inherited from this era continue to shape Senegalese society. Schools, for example, remain largely modeled on the French system. But behind this continuity lies a profound inequality: a relationship of dependency, where the center decides and the periphery adapts.

Senegal declared its independence in 1960. Yet, its ties with France have not been erased. Military cooperation, economic agreements, cultural presence: everything seems to point to an incomplete independence. France maintains bases, influences political decisions, and controls part of the economic flows. Behind the rhetoric of friendship lies a neocolonial mechanism.

Trade between the two countries rarely benefits Senegalese workers. French companies dominate key sectors such as energy, telecommunications, and banking. Profits flow back to Paris, leaving few local benefits. Fishing agreements illustrate this injustice: French vessels exploit Senegalese waters, depleting resources and undermining local fishermen.

The Senegalese diaspora in France constitutes much more than a simple economic relay; it embodies a paradoxical articulation between material necessity and political invisibility. The massive and regular financial flows compensate for the deficiencies of local social systems and keep entire sectors of Senegalese society afloat. Yet, this vital function is almost systematically reduced to its strictly monetary dimension, as if the citizen contribution, the forms of mobilization, the democratic demands made from exile had no legitimacy. Thus, a persistent asymmetry is established: the circulation of capital is recognized, valued, sometimes celebrated, while the circulation of voices remains restricted, confined to the margins, deprived of a real space in the political field.

The French language occupies a central place in Senegal. But it coexists with Wolof and other national languages, which carry memory and popular resistance. La Francophonie, presented as a cultural wealth, often serves to mask relations of domination. Yet Senegalese artists, writers, and musicians use this heritage to subvert it, transforming the tool of the former colonizer into a critical weapon.

Digital technology also illustrates these relationships of dependency. International platforms dominate the market, marginalizing local initiatives. Sites like 20Bet login , originating from abroad, attract young people in search of entertainment and quick profits. But behind the gambling lies capitalist logic: capturing revenue in a country where economic prospects remain limited. Online gambling thus becomes a metaphor for our shared history: promises of modernity, but persistent exploitation.

Senegalese leaders oscillate between cooperation and protest. On the one hand, they benefit from diplomatic and military support from Paris. On the other, they must deal with a youth population demanding a clear break with the old colonial logic. Social movements remind us that sovereignty cannot be a mere slogan: it must translate into concrete political choices, free from external pressures.

The Franco-Senegalese relationship cannot be isolated from the African context. France seeks to maintain its influence, while other powers such as China and Turkey advance their pawns. Senegal is becoming a competitive arena where foreign interests take precedence over popular needs. The struggle for true independence is thus expanding into a global battle to escape imperialist logic.

In official memory, colonization is often reduced to cultural and economic “exchanges.” But what about the humiliations, the dispossessions, the massacres? These invisible legacies still structure current inequalities. Behind every road, every building inherited from the colonial period, lies the forced labor of entire generations. France speaks of a “shared history,” but this vocabulary erases the violence. It is not a shared history; it is an imposed history.

Even after independence, economic dependence persisted. The CFA franc, a monetary instrument designed in Paris, is the most striking example. Officially, it guarantees stability and security. In reality, it locks Senegal into a system where its wealth primarily serves external interests. Behind the promises of modernization, there is an economic barrier that limits popular sovereignty. Here again, this is no accident: it is the continuation of domination.

We often forget that the Franco-Senegalese relationship is also inscribed in the body. Senegalese riflemen, forcibly conscripted or under the promise of gratitude, shed their blood for a homeland that was not theirs. Upon their return, many were scorned, poorly compensated, and marginalized. These collective wounds persist, passed down within families, reminding us that memory is not just a matter of monuments, but also of open scars.

The shared history between Senegal and France is not a harmonious one. It remains one of wounds, struggles, fractured memories, and missed opportunities. Behind every official speech praising "cooperation" lies the weight of forced labor, resource monopolization, and broken promises.

This history is not frozen in books: it still weighs on daily life, on migration rules, on economic imbalances, on cultural hierarchies inherited from colonization.

But nothing is sealed for eternity. Memory remains alive, and resistance accompanies it. Senegalese youth are taking to art, the streets, and social media to speak out again. In France, too, voices are being raised to crack academic myths, to reveal what was long hidden. The bond between the two countries could remain one of domination; it can also become something else, if it is rebuilt from the bottom up, by those who refuse to be forgotten and demand justice.

Commentaires (3)

Nous sommes le Gaabu,

Nous sommes le Mandé,

Nous sommes le Songhaï,

Nous sommes l'Afrique de l'Ouest.

La langue Anglaise est sans doute mil fois plus utile que la langue française c'est pourquoi il faut choisir l'Anglais sur le français comme langue officielle à côté du Wolof,

pas parce qu'on aime l'Angleterre ou les États-Unis mais parce que la langue Anglaise est devenue universelle, dans tous les pays du monde l'anglais si ce n'est pas la langue officielle du pays donc est étudié comme la première langue étrangère après la langue du pays.

Donc au lieu de perdre le temps d'apprendre le français comme langue officielle après l'anglais comme première langue étrangère supprimons le français, pourquoi fatiguons nous à apprendre une langue inutile et impopulaire, faisons comme tous les pays Asiatiques, Européens etc...

Apprenons nos propres langues nationales, remplaçons le français par le Wolof puisque c'est la langue la plus parlée et plus comprise dans notre pays et après une seule langue européenne comme l'anglais est la plus utile plus universelle plus facile plus répandu plus populaire etc... que le français même en France à partir du lycée l'anglais est obligatoire et aussi même en France pour beaucoup de boulots il faut absolument maîtriser l'anglais,

donc c'est logique qu'on laisse le français au profit de l'anglais, après nos chères langues comme tous les pays du monde.

L'anglais est la langue la plus utilisée dans tous les domaines, notamment les affaires, la science, le commerce, le tourisme, la recherche, la technologie, les médias, les communications internationales etc... est étudiée comme la première langue étrangère dans tous les pays du monde y compris ceux qui ont des relations tendues avec les pays anglo-saxons comme États-Unis ou l'Angleterre. Surtout quand on voyage dans le monde qu'on va réellement connaître l'importance de l'anglais sur le français

Il est également important de ne pas négliger l'importance des langues maternelles. Apprendre sa langue maternelle est essentiel pour le développement personnel et culturel, et peut même faciliter l'apprentissage d'autres langues.

Renforçons nos langues nationales, l’anglais, la technologie et les sciences au lieu de perdre du temps avec la langue française qui ne cesse de perdre de l’influence, le Sénégal ferait mieux de se mettre à la marche du monde. La maitrise de l’anglais par des autorités françaises, à commencer par le président, devait nous interpeller. Des manifestations se tiennent au cœur de Paris (au palais des congrès, aux différents parcs des expositions, Station F etc............. avec l’anglais comme langue de travail.

Aujourd’hui, la science est en anglais, l'universel est en anglais, même dans les universités françaises.

A l’échelle universitaire, on le sait, le système LMD est devenu un modèle quasi-mondial et aussi une contrainte mondiale. Poussé par les instances internationales: Banque mondiale et UE. Ce système LMD a été conçu pour la mobilité des étudiants (système Erasmus dans l’UE). Cette mobilité s’appuie essentiellement sur l’enseignement anglais, puisque les étudiants doivent faire des enseignements semestriels dans des pays différents (par exemple un français peut faire un semestre au cours des trois années de licence ou des deux années de master de la même spécialité en Hongrie ou au Danemark, essentiellement en anglais). Le LMD est appliqué pour le moment artificiellement, dans sa logique et philosophie de base mobilité, favorable au rapprochement des peuples (européens) et l’échange d’étudiants.

Pendant ce temps, nos autorités, au plus haut sommet, continuent de porter des casques de traduction dans toutes les rencontres internationales. Les horizons de nos diplômés sont limités, la recherche plombée faute d’un niveau acceptable en anglais.

Le moment est venu d’arrêter cette langue et de renforcer l’anglais, les sciences et la technologie. Mais cela demande à la fois une vision et du courage. Il faut se donner un délai pour supprimer cette langue dépassée.

Il faudra du courage pour faire face aux oppositions qui ne manqueront pas avec les Senghoriens, Senghoristes et les esclaves du salon.

Même si on aime la langue de Molière, avec laquelle on s'est tous formé et qui nous émeut toujours. Ce n'est pas une question d'amour pour une langue, mais de réalisme. Prendre en considération les intérêts stratégiques de tout un peuple. Accéder au monde, sortir de sa coquille, s’adapter et surtout progresser: tel est l’enjeu d’avenir. Mais, il faut le savoir à l’avance, si le SÉNÉGAL décide d’opter pour l’anglais, comme langue officielle à l’avenir, il faudrait s’attendre à voir descendre à Dakar toute l’armada des dirigeants politiques et diplomates français, ainsi que leurs intermédiaires, en vue de dissuader le SÉNÉGAL de le faire.

Il faudrait donc s’y préparer à l’avance.

Le passage d’une langue à une autre n’est pas nouveau. De nombreux pays ont réussi leur transition linguistique, en passant d’une langue étrangère à une autre, et pour des raisons diverses.

L'ex Indochine Française:

C'est à dire Le Vietnam, le Cambodge et le Laos ont retiré la langue française comme langue officielle ont mis leurs langues nationales à sa place et l'anglais comme première langue étrangère

depuis les années cinquante.

Au Rwanda, on est passé par étapes, du français à l’anglais. Ils ont introduit l’anglais en 1994 après le génocide (ils tiennent la France pour politiquement responsable des violences de cette période), puis en 2003, l’anglais est devenu carrément 2ème langue officielle après le Kinyarwanda et langue du travail, Kinyarwanda qui est la première langue nationale et première langue officielle du pays.

L'Algérie depuis trois ans a retiré le français comme première langue étrangère et a mis l'anglais comme première langue étrangère après les deux langues du pays:

L'arabe langue nationale et officielle et le Tamazight comme deuxième langue officielle.

Au Maroc L'anglais est de plus en plus enseigné et sa maîtrise est perçue comme cruciale pour l'avenir, en particulier par les jeunes. Le ministère de l'Éducation a décidé de généraliser son apprentissage Ils voient l'anglais comme la langue des sciences, des affaires et de l'internet, et pensent que le passage à l'anglais bénéficierait à l'ambition du Maroc en tant que pôle international.

En Tunisie

Une mutation visible dans la société

Dans la rue, les médias et même le dialecte tunisien, les emprunts à l’anglais se multiplient.

De plus en plus d’entreprises privilégient la communication bilingue arabe-anglais, au détriment du français.

Pour beaucoup de jeunes, l’anglais est perçu comme la langue de l’avenir, celle qui ouvre les portes d’un monde globalisé. Le français, lui, conserve une image liée au passé colonial ou à une élite traditionnelle, ce qui le rend moins attractif pour une génération en quête de modernité et d’ouverture.

Suisse Germanique: 70/100 de la population Suisse,

L'aéroport de Zurich a supprimé la plupart des annonces en français, ne conservant que l'allemand et l'anglais pour réduire le bruit et améliorer le confort des passagers, conformément à une tendance internationale. Des exceptions subsistent pour les vols vers des destinations francophones et pour les messages de sécurité. La version française du site web de l'aéroport a également été abandonnée car elle était peu consultée.

Zurich va arrêter d’enseigner le français dans les écoles primaires

Zurich est le dernier canton suisse germanophone à remettre en question la politique suisse d’enseignement du français dès les premières années de scolarité.

Ce septembre 2025 son conseil cantonal a voté la suppression des cours précoces de français, rejoignant ainsi Appenzell Rhodes-Extérieures, qui avait pris une décision similaire plus tôt cette année. Des propositions visant à repousser l’enseignement du français au secondaire sont également en discussion dans d’autres cantons germanophones, notamment Saint-Gall, Thurgovie et même le canton bilingue de Berne.

La Suisse compte trois principales langues nationales : l’allemand: 70/100, le français: 21/100 et l’italien: 08/100 Toutefois, seule une minorité de Suisses maîtrisent plus d’une langue nationale.

De plus en plus, les jeunes privilégient l’anglais comme deuxième langue plutôt qu’une autre langue nationale.

En Suisse romande cette décision est perçue comme une gifle. Beaucoup sont particulièrement irrités que Zurich conserve l’anglais précoce tout en supprimant le français précoce.

Mais peu sont surpris.

En Suisse romande, l’allemand est bien ancré dès l’école primaire, même si les résultats restent mitigés : peu deviennent vraiment bilingues, car beaucoup n’utilisent jamais ce qu’ils ont appris à l’école.

La Belgique compte deux principales régions linguistiques la Flandre: le néerlandais comme langue officielle 60/100 de la population du pays

Et la Wallonie: le français comme langue officielle 40/100 de la population du pays.

L’anglais est désormais la langue la plus parlée parmi les jeunes Belges

L’anglais est devenu la langue la plus parlée par les jeunes (âgés de 15 à 34 ans) en Belgique. En 2024, il a dépassé les deux langues officielles du pays.

Un peu plus de six personnes sur dix (60,5 %) en Belgique âgées de 15 à 34 ans déclarent avoir une « bonne à très bonne connaissance » de l’anglais, contre 57,1 % pour le néerlandais et 56,3 % pour le français.

Le Canada c'est dix provinces et trois territoires,

seulement une province le Québec parle le français.

Le reste c'est à dire 9 provinces et 3 territoires parlent l'Anglais.

Verdict

Il y a bel et bien déclin du français au Québec: les démographes s’entendent sur ce point. Mais leur opinion diffère sur sa rapidité et sur le rôle de l’immigration dans ce déclin.

Participer à la Discussion

Règles de la communauté :

💡 Astuce : Utilisez des emojis depuis votre téléphone ou le module emoji ci-dessous. Cliquez sur GIF pour ajouter un GIF animé. Collez un lien X/Twitter ou TikTok pour l'afficher automatiquement.