Sur les traces du village d'origine d'Omar Ibn Saïd, un homme lettré capturé et vendu comme esclave en 1807 aux Etats-Unis

It's a fascinating story that continues to generate a lot of discussion in Africa and the United States.

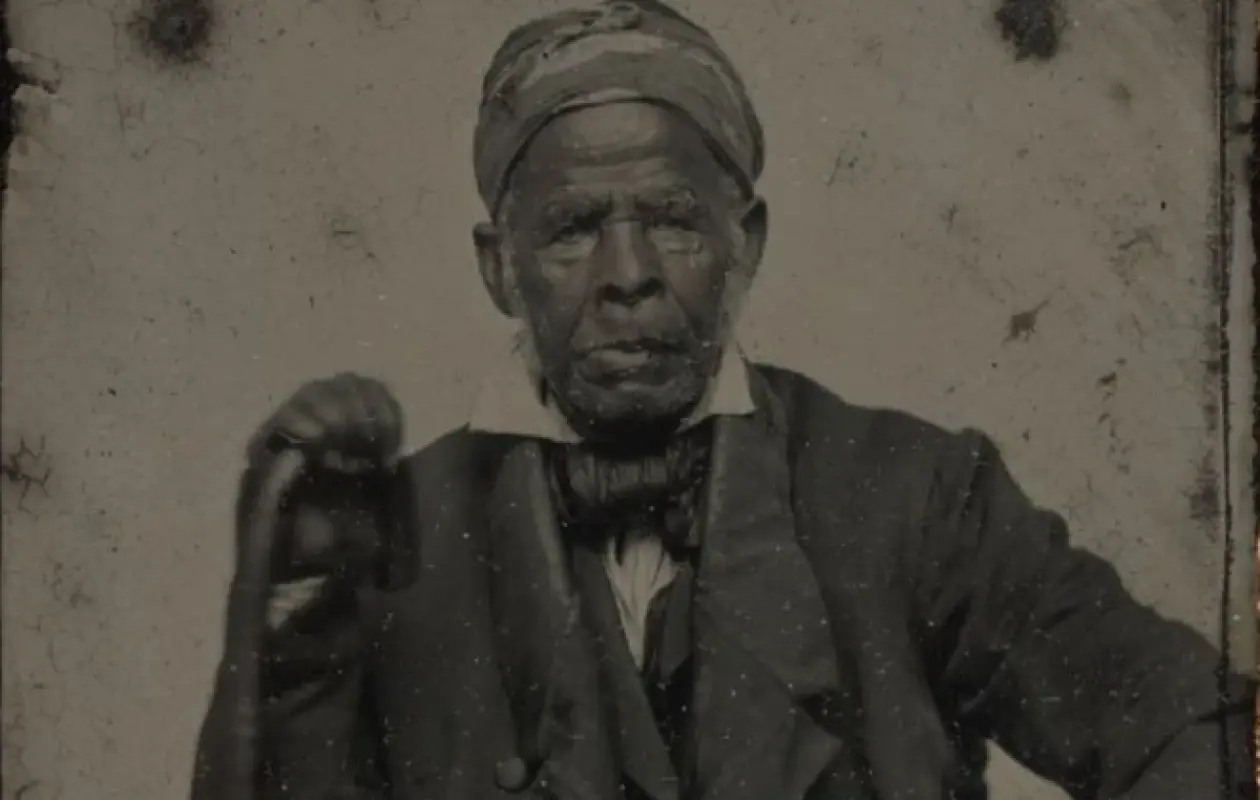

This is the story of Omar Ibn Said. Born in Fouta Toro (Senegal) around 1770, he was captured and sold at the age of 37 as a slave in Charleston (South Carolina - United States).

Having escaped his master, he fled before being apprehended and imprisoned in Fayetteville, North Carolina. From his place of detention, the man began writing on the prison walls. News of the slave scribbling in strange handwriting spread throughout the town. He was then bought by another master.

Since the discovery of his Arabic manuscripts recounting his life and origins, American and Senegalese researchers have embarked on a quest to uncover his roots. A group of Senegalese researchers believes they have finally identified the village in question, located in the heart of Fouta Djallon, in northern Senegal.

In one of his autobiographical manuscripts, Omar Ibn Said speaks of his life. He writes: "Before my coming to the land of the Christians (United States), my religion was that of Muhammad, the Prophet of Allah. May Allah bless him and grant him peace." He explains that he made the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca.

Speaking of his birth, he states that he was "born in Fouta-Toro, between the two rivers" and claims to have studied in Boundou (a province in eastern Senegal) for 25 years.

“After my studies, I returned home for six years before an army invaded our country. They killed many people. They captured me and sold me to a Christian who took me on a large ship,” wrote Omar Ibn Said.

He was put on a ship bound for the other side of the Atlantic, and after a month and a half voyage, he was disembarked in Charleston where he was sold.

"There, they sold me to a small, weak and wicked man named Johnson, a complete infidel who had absolutely no fear of God," wrote Omar Ibn Said.

A victim of abuse like most slaves, he escaped a few years later.

"I am a small man and incapable of doing hard work. So I ran away from Johnson's hands and, a month later, I arrived at a place called Fayd-il (Fayetteville)," he relates in his writings before recounting the circumstances of his arrest.

"At the new moon, I went into a church to pray. A young boy saw me and rode off to his father to tell him that he had seen a Black man in the church. A man and another man with him on horseback arrived, accompanied by a pack of dogs."

Arrested and imprisoned for "sixteen days and sixteen nights", he was bought by a "named Jim (James) Owen, who happens to be the brother of the governor of North Carolina.

In contrast to his first master, described as a "wicked infidel", James Owen is described as a "good man who reads the Gospel".

"I am still under the protection of Jim Owen, who does not beat me, does not insult me, and does not subject me to hunger, nudity, or forced labor," he wrote on the last page of his autobiographical manuscript, specifying, however, that "I cannot work hard because I am a small and sick man."

In his manuscripts, he mentions a conversion to Christianity while continuing to refer to the Quran.

For Mamarane Seck, this aspect is "disturbing and raises many questions that need to be clarified".

Mamarame Seck is a lecturer and researcher at the Fundamental Institute of Black Africa (IFAN) at Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar. He is also the curator of the Historical Museum of Senegal in Gorée.

With a group of Senegalese historical researchers, he embarked on a search for the village of origin of Omar Ibn Said, now made famous by the discovery of his Arabic manuscripts, currently exhibited at the Library of Congress.

Reached by phone by BBC News Africa, he tells us that he believes he has identified the village of origin of Omar Ibn Said after research carried out in Fouta in northern Senegal.

To carry out his research, he obtained a copy of the Arabic manuscripts carefully preserved at the Library of Congress.

"By having the text (in Arabic) of Omar Ibn Said reread by the people of Fouta, I was convinced that this text would reveal things to us that others (English translators) have not necessarily understood," explains Dr. Mamarane Seck.

Armed with the manuscripts and the details contained in these documents, he conducted several interviews in Fouta with notables and scholars in Arabic to try to extract as much information as possible about manuscripts written with calligraphy in Maghribi style (generally adopted by marabouts and Koranic schools in West Africa).

As a researcher, the geographical descriptions contained in the manuscripts have also been of great importance.

''It is not only the autobiographical manuscript, but there are also other documents of letters written by the slave'' notes Mamarane Seck adding that in one of these letters which dates from 1819, Omar Ibn Saïd said somewhere that he wanted to return to Africa to a village whose mention on the manuscript had been read ''Coppé'' by an imam.

"That's what prompted me, after visiting other places in Fouta, to go to Coppé and focus mainly on this village to find out to what extent it could be the village of origin of Omar Ibn Saïd," the Senegalese academic recounts.

''In the history of the village,' says Mamarane Seck, 'its geographical position, the reading of its name by a respected imam and other testimonies collected on the history of the village, everything indicates that Coppé could be the village of origin of Omar Ibn Saïd''.

"Omar says in his writings that he comes from a place (Coppé) located between the two rivers. This description refers us to the Island of Morphile, which is between the Senegal River and its tributary the Doué," he specifies.

Speaking of his capture and subsequent sale as a slave to a white man, Omar Ibn Said said of "a band of unbelievers who came to attack his village and killed many people and walked with me to the river."

"If you look at the geography of the village, it all fits together," argues Dr. Mamarane Seck.

The year of the capture of Omar Ibn Said (1807) also corresponds to a historical fact well known to Senegalese historians.

"Yes, it was 1807, it was the end of the reign of Abdul Qadir Kan who was the first Almamy of Fouta Toro," the Senegalese academic points out.

"He (Almamy) was known for having put an end to the enslavement of Muslims. In fact, he was assassinated because of this," he recalls, before adding that "it was common at that time to see attacks on enemy villages to take captives."

It all started with the discovery of a series of 15 documents written in Arabic by Omar Ibn Said himself.

Having fallen into the hands of Theodore Dwight, abolitionist and founder of the American Ethnological Society, the manuscripts were translated into English by Dwight and his academic colleagues and members of the American Colonization Society in 1925.

The translated documents were lost and were found in 1995, seventy years later.

Since then, they have aroused the curiosity of visitors to the Library of Congress, particularly researchers and the African-American community.

Omar Ibn Said lived as a slave until his death in 1864 at the age of 94. For the Senegalese academic, his story is of twofold interest.

"As a member of a research group on the return of cultural property, it is necessary that the communities themselves be involved in this search for the origin of the slave," he said.

"It is in this context that I began to work on this subject, in particular by trying to bring back the text to share it with the people of Fouta because it was written by one of their own, even if he wrote it while being a slave, for me it is a common heritage of the population of Fouta," explains Mamarane Seck.

"Secondly, with the text of Omar Ibn Said, we can better understand first the conditions of his captivity and slavery in the sub-region," he said, stressing that research aimed at finding his tomb in the United States with American colleagues is underway.

Commentaires (8)

Deux grandes difficultés rendent souvent difficiles la reconstitution de l'opinion des populations qui peuplaient le Sénégal moderne : la transmission des faits historiques par les griots est de plus en plus difficile et souvent hagiographique, l'illettrisme était la règle sous nos tropiques.

C'est donc, malheureusement pour eux, une grosse chance pour nous que des lettrés arabophones venant du Fuuta ou du Bundu aient laissé des traces écrites de leur périple transatlantique

Du courage aux chercheurs !

.

Participer à la Discussion

Règles de la communauté :

💡 Astuce : Utilisez des emojis depuis votre téléphone ou le module emoji ci-dessous. Cliquez sur GIF pour ajouter un GIF animé. Collez un lien X/Twitter, TikTok ou Instagram pour l'afficher automatiquement.