Paul Sédar Ndiaye : « L'amour n’est pas une fête dans le calendrier, c'est un toit que l'on construit brique par brique »

On the occasion of Valentine's Day, a worldwide celebration of love every February 14th, many questions arise about its true meaning, its effects on couple life and its place in our contemporary societies.

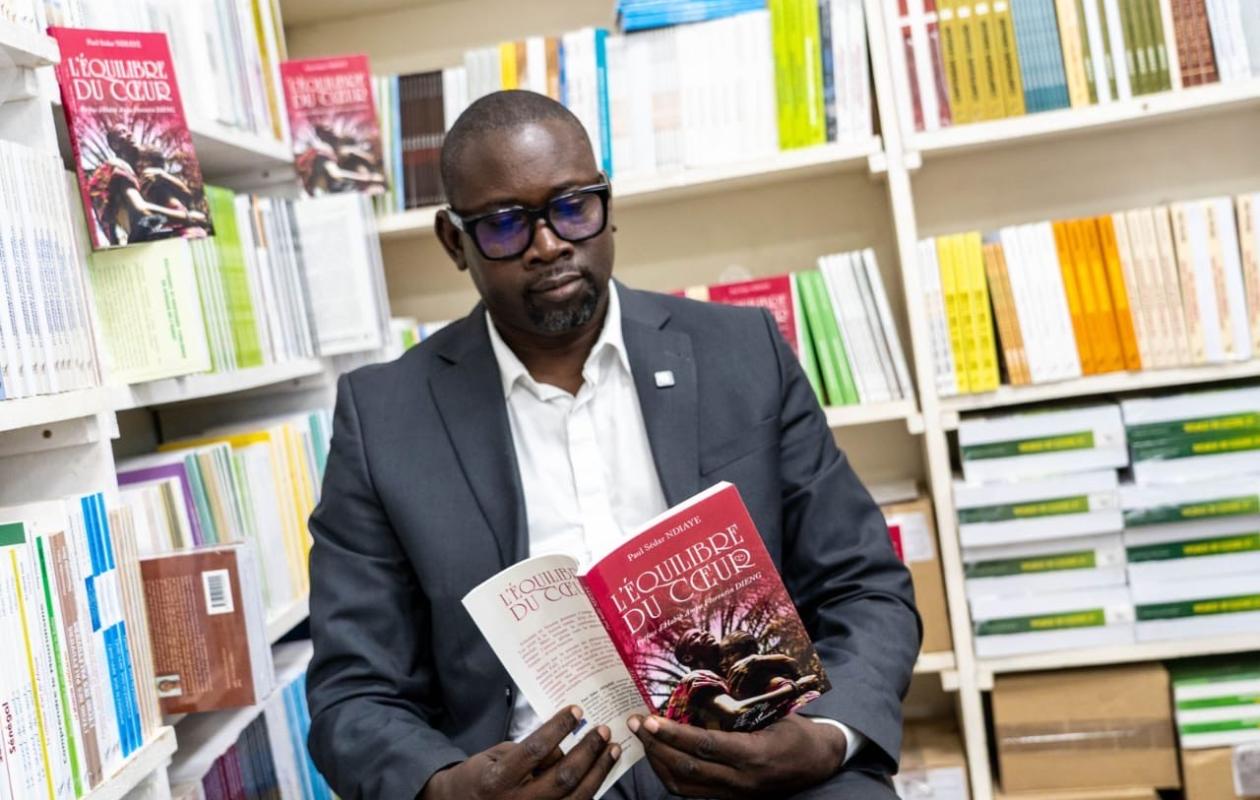

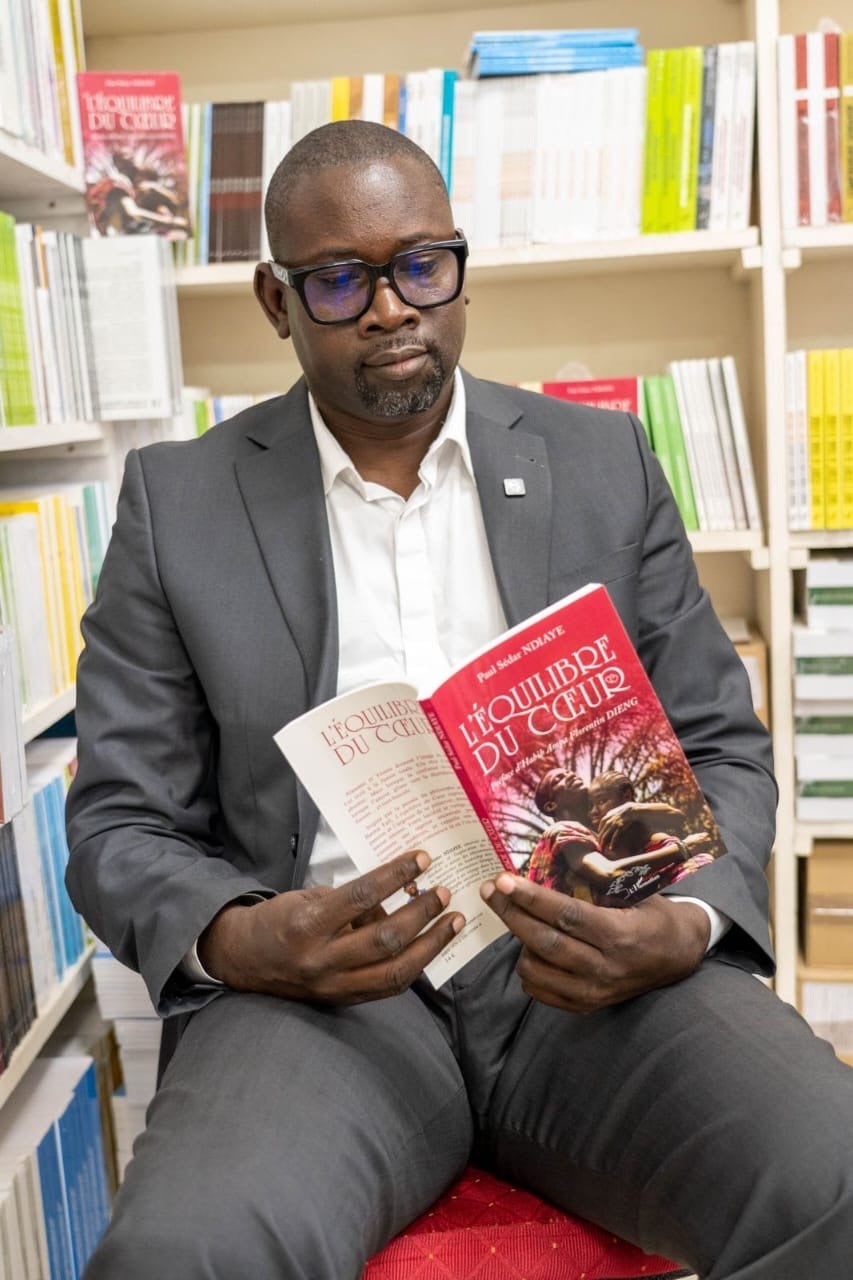

In this interview with Seneweb, Paul Sédar Ndiaye, author of the recently published novel L'Équilibre du Cœur, offers a critical reading of this celebration in light of the marital dynamics he explores in his work.

He analyzes the tensions between love, social expectations and cultural heritage, while questioning the foundations of the modern couple in the face of the symbolic and emotional pressures that crystallize on February 14th.

You recently published, a few weeks ago, The Balance of the Heart. Did this novel originate from a social observation, a personal experience, or a theoretical reflection on the couple?

This novel was born of both frustration and fascination. I was deeply saddened by the high number of promising relationships that end badly due to persistent misunderstandings. At the same time, I felt a profound curiosity to understand how, in a society that emphasizes love, mistrust continues to be taught.

It stems first and foremost from a careful observation of contemporary Senegalese society, where couple models are undergoing a profound redefinition, torn between aspirations for modernity and the weight of tradition. As a manager, I've learned that unspoken issues are the poison of any organization. I wanted to show that this is even more true in the smallest and most complex of organizations: the couple.

There is, of course, a personal element to this. Not in the sense of an autobiography, but rather a question that has long preoccupied me: how to reconcile love, which is essentially a form of surrender, with the need to preserve oneself as an individual? Finally, there is a philosophical dimension. My first essay, Téranga, explored leadership through the lens of our ancestral values. With The Balance of the Heart, I extend this approach by applying the ancient wisdom of Kocc Barma Fall to the most intimate question of all: that of the couple. Ultimately, this book was born where my expertise as a manager and my anxieties as a man converged.

The title evokes a constant tension: what “balance” are you trying to question?

The balance I'm questioning is the extraordinarily fragile one between fusion and independence. It's the balance between the "we" of the couple and the "I" of the individual. In our culture, love is often perceived as total fusion, an unreserved gift of oneself. But this view carries within it a danger: the dissolution of the individual, the loss of their own identity.

The novel explores this fine line: how far can one go in self-sacrifice without betraying oneself? How can one trust another without giving them the keys to their own destruction? The balance of the heart is not a static state; it is a permanent dance between two poles, a constant negotiation between love for the other and self-respect.

In the novel, love seems fragile in the face of the weight of tradition. Do you think modern marriage in Senegal is in crisis?

I wouldn't call it a "crisis," but rather a profound transformation. Marriage in Senegal today is the scene of a clash between several models. On one side, the traditional, community-based model, where the couple is a family affair. On the other, the Western, individualistic model, based on romantic love and personal fulfillment.

The problem is that we often try to reconcile the two without realizing it. We crave the passion of the Western model, yet remain bound by the constraints of the traditional one. It's this uncontrolled hybridization that creates tension. My book doesn't say that love is fragile; it says that it becomes fragile when caught between conflicting expectations.

The maxim attributed to Kocc Barma Fall plays a central role. Why was it chosen to be integrated into the plot?

Kocc Barma Fall is our Senegalese Shakespeare. His maxims are the essence of our cultural DNA. By choosing this one, I wanted to put our heritage on the couch. This phrase is a mirror: it reflects our wisdom, but also our contradictions. It's a key to understanding why, in Senegal, love is always a political matter, a negotiation between the heart and heritage.

This phrase, "One must love a woman, but beware of trusting her completely," is both a treasure trove of folk wisdom and a potential source of mistrust. By incorporating it into the plot, I wanted to show how an ancient saying can become a character in its own right within a relationship. It embodies this duality: an immense capacity for love, but also a structural mistrust of women. Kocc Barma Fall didn't leave us a commandment; he bequeathed us a mirror. I simply dared to look into what was reflected in it.

In your opinion, do tradition and family ties protect the couple or do they sometimes contribute to confining them?

Both—that's the crux of the matter. Tradition and family can be a protective cocoon. In times of crisis, the community provides support and mediation. It's an immense strength, a safety net. But this cocoon can also become a gilded cage.

The omnipresence of family and the weight of societal expectations can stifle intimacy. Individuals are compelled to put the interests of the group before their own. In my book, Alassane's mother wants to protect her son, but she traps him in an outdated worldview that ultimately destroys him. Protection then becomes a form of control.

In this novel, Yeuma is judged more than listened to. Is this a deliberate critique of society's view of married women?

Absolutely. Yeuma is at the heart of this criticism. She's brilliant and loving, but as soon as difficulties arise, she becomes the perfect scapegoat. She's judged on her ambitions, her management of the household, her relationship with money. She's no longer a person, she's a status: "the wife."

Women are expected to be pillars of strength, yet we spend our time undermining their foundations. Yeuma embodies this silent injustice. They are expected to be both submissive traditional wives and fulfilled modern women—an untenable paradoxical demand.

Do you think that women are often presumed guilty in marital conflicts?

Unfortunately, yes. It's a patriarchal legacy. When a couple is struggling, the first reflex is to look for the woman's "fault": did she have enough "mougn" (patience)? The man, on the other hand, is more often seen as a victim of his impulses or of a woman who didn't understand him. This presumption of guilt is a double punishment for women. I grew up surrounded by strong women who carried the world on their shoulders. Through Yeuma, I wanted to pay tribute to their resilience.

Does the novel argue for a redefinition of the relationships of trust between men and women?

Yes. The novel argues for a clear-sighted trust. A trust that is not blind, but a conscious and renewed choice. Redefining trust means accepting that the other person has their own private space and autonomy, and that this is not a threat, but a condition for the survival of the couple. It means moving from a trust based on control to a trust based on mutual respect for individuality.

Money appears to be a factor in the breakdown of relationships. Has it become central to marital stability?

Money isn't a cause of breakups in itself; it's a revealer. Money doesn't destroy couples; it simply reveals whether they were built on rock or sand. In an increasingly materialistic society, success is measured by possessions. This pressure impacts couples: the man is expected to be the provider, the woman the manager. The real problem isn't money itself, but the lack of communication about it; it's a taboo that poisons relationships.

Does Alassane's social status influence his fear of betrayal?

Extremely. His success as an architect paradoxically makes him more vulnerable. His fear of betrayal is social: he's terrified of being demoted, of being seen as a man who "can't handle his wife." His status is armor, but also a prison that amplifies his paranoia tenfold. The gilded cage, the greater the fear that it will open.

Is the gaze of others more destructive than internal conflicts?

The opinions of others fuel inner conflicts. A private problem can be resolved, but when it becomes a matter of honor and reputation in front of family or friends, destruction becomes inevitable. The noise of the world often prevents us from hearing the whispers of our own hearts. Alassane and Yeuma are forced to play a role to save face, which prevents any honest conversation.

Is Yeuma a character of resistance or sacrifice?

She is both. She begins with sacrifice, embodying traditional resilience. But faced with injustice, she transforms. Yeuma starts as a martyr and ends as a warrior. Her resistance lies in refusing to be destroyed. She understands that the greatest love is the love we have for ourselves. She teaches us that the greatest strength is not in enduring everything, but in knowing when to stop enduring.

What message do you want the reader to take away when they close the book?

I hope the reader will ask themselves, "And where do I find my balance?" The greatest tragedy isn't not being loved, but failing to love oneself for fear of disappointing others. I hope this book will encourage couples to ask the difficult questions that ultimately save lives.

Do you think trust is still possible in a world dominated by doubt?

It is more necessary than ever. Trust is an act of resistance, a courageous choice. It's not about believing the other person is perfect, it's about betting on the best in them. It must be an ongoing process, a patient craft based on transparency and dialogue.

Does Valentine's Day really strengthen romantic bonds?

It's a magnifying glass. For some, it's a wonderful opportunity to break free from routine. But for many, it's a commercial pressure that imposes a standardized vision of love. It can create unrealistic expectations and become a tool for social comparison. Sometimes we're more passionate about the proof of love than about love itself.

Has this festival become an obligatory event?

Yes, because it touches on the need for recognition. Celebrating Valentine's Day is about showing the world (especially on social media) that you're part of the "club" of happy couples. It's also a symbol of cultural globalization that is superimposed on our own traditions.

Is love proven by celebrating such a day?

No, a thousand times no. Love is a marathon, not a sprint. The greatest proof of love isn't a bouquet of flowers on February 14th, it's a listening ear after a difficult day or a kind gesture on an ordinary morning. Love isn't a holiday on the calendar, it's a roof built brick by brick, 365 days a year.

Commentaires (6)

Participer à la Discussion

Règles de la communauté :

💡 Astuce : Utilisez des emojis depuis votre téléphone ou le module emoji ci-dessous. Cliquez sur GIF pour ajouter un GIF animé. Collez un lien X/Twitter, TikTok ou Instagram pour l'afficher automatiquement.